Accountability Is the One Word Missing From Most Project Plans

Ask a project team who is accountable for a decision and you’ll often get silence, a job title, or a steering committee. Rarely do you get a name.

That gap between responsibility and accountability is where many projects quietly unravel.

On paper, accountability is everywhere. RACI charts. Governance diagrams. Delegations of authority. The language is familiar and reassuring. In practice, accountability is often diffused to the point where no one truly owns the outcome.

Everyone is involved. No one is accountable.

Responsibility is easy to assign. Accountability is not. Responsibility can be shared. Accountability cannot. Yet many project environments behave as if the two are interchangeable.

They aren’t.

In complex projects, ambiguity around accountability feels polite at first. It avoids conflict. It keeps relationships smooth. It allows decisions to be deferred while more information is gathered. Over time, that ambiguity becomes protective. It shields underperformance. It blurs ownership. It creates space for problems to circulate without being resolved.

When things go wrong, the language shifts. “The team decided.” “Governance endorsed.” “It was a collective view.” Accountability dissolves into process.

This is not a failure of intent. It is a structural failure.

Many projects are designed to distribute risk so widely that no single person feels safe making a hard call. Committees exist to reduce exposure, but often end up diluting responsibility. Decision-making slows, not because people don’t care, but because the cost of being accountable feels too high.

In those environments, the safest position is to contribute without owning.

RACI charts are often held up as the solution. In theory, they clarify who is responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed. In practice, they frequently reinforce ambiguity. Boxes get filled. Roles get agreed. And when a real decision arrives, the chart is nowhere to be found.

The issue is not the tool. It is the reluctance to attach a name to an outcome.

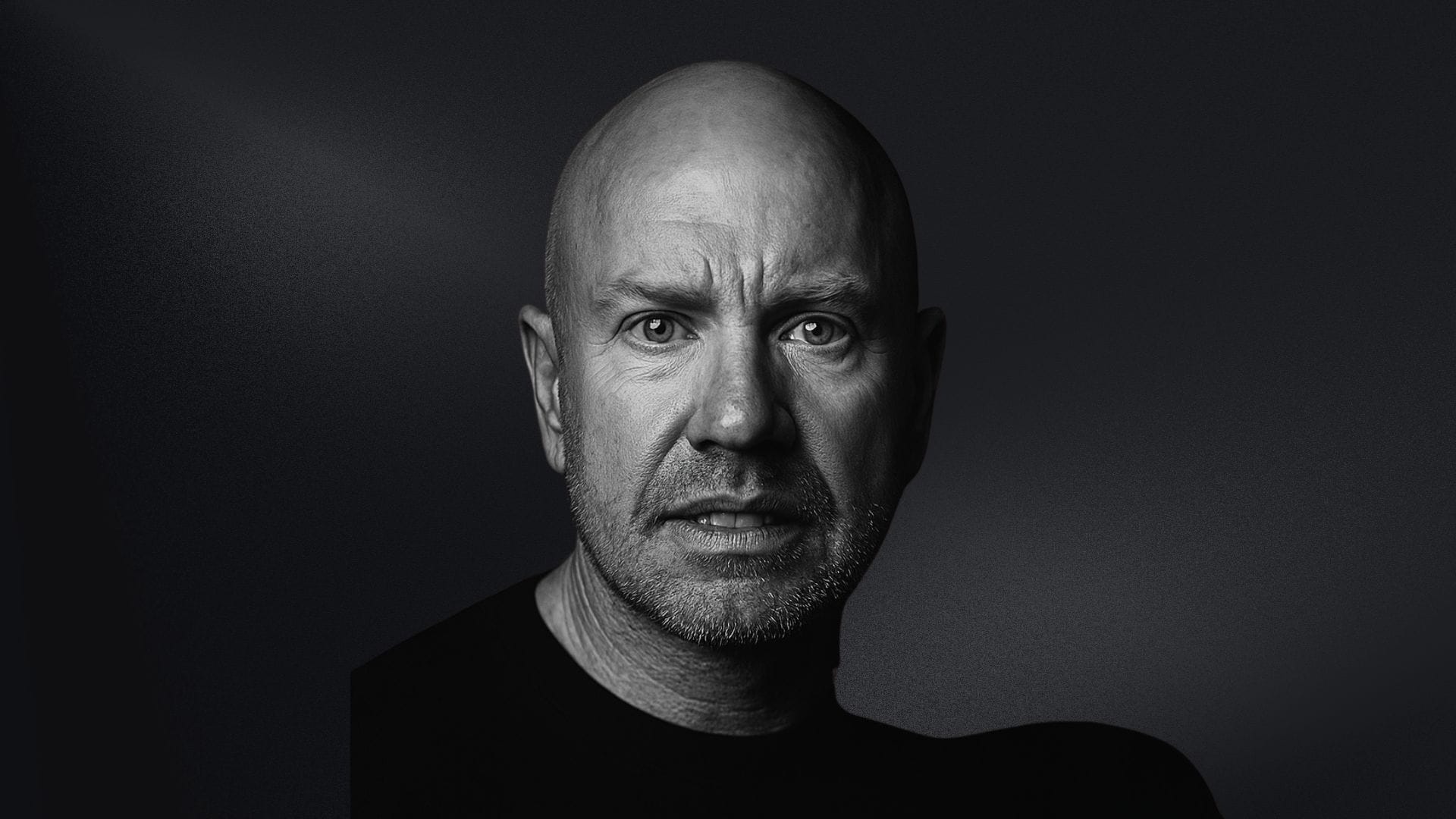

Real accountability is uncomfortable. It requires someone to say, “This is my call,” knowing that the decision may be unpopular, incomplete, or wrong in hindsight. It requires authority to be matched with consequence. Without that, accountability is symbolic.

In high-performing delivery environments, accountability is explicit. Not because the structures are simpler, but because the expectations are clearer. Decisions have owners. Escalations have thresholds. When a call is made, it is recorded as such.

This does not eliminate disagreement. It makes disagreement productive.

One of the quiet advantages of clear accountability is speed. When it is obvious who owns a decision, conversations change. Issues move forward. Trade-offs are confronted earlier. Waiting for consensus is replaced with seeking advice, then deciding.

That distinction matters.

Projects stall not because people lack information, but because no one is empowered to act on it. When accountability is vague, momentum drains away through caution.

Accountability also changes behaviour after decisions are made. When someone owns an outcome, they stay engaged. They monitor consequences. They adjust when reality shifts. When ownership is collective, follow-through is often assumed rather than ensured.

This is why many projects appear busy but drift strategically. Activity continues, but direction weakens.

Good project managers understand this dynamic. They don’t just manage schedules and risks. They pay attention to where accountability sits, and where it doesn’t. They notice when decisions float between forums. They recognise when language becomes evasive.

Surfacing that gap is rarely comfortable. Asking, “Who owns this?” can feel confrontational. In reality, it is one of the most constructive questions a project can ask.

Accountability does not mean acting alone. It means acting with clarity.

In 2026, projects are too complex, too visible, and too consequential to rely on implied ownership. The cost of ambiguity is simply too high. Decisions will always involve uncertainty. Accountability determines whether that uncertainty is managed or avoided.

Most projects do not fail because people don’t work hard. They fail because accountability is diluted just enough for problems to circulate without resolution.

Plans are full of tasks, milestones, and dependencies. What they often lack is a clear answer to one simple question.

When it matters, who is accountable?